FINE old military stations like the Presidio of San Francisco sufficed to prepare an Army for battle against Sioux Indians. But the many great wartime camps needed to ready onslaughts against the Hordes of World Fascism had to be jerry-built upon ever more drab stretches of land, promoted by local Congressmen: such was Camp Tyson, Tennessee. The troop train from Camp Grant rumbled into a village next to the Camp, named by its deluded pioneers "Paris", now redesignated from behind the train's grimy windows unequivocally, "Asshole of the World."

Futile jerky attempts to chug the train in close to the mud flats of the Camp proper ended amid a disordered collectivity of shacks and houses. The soldiers, for that's what they now were, obeyed various shouts to detrain, under the impassive eyes of lolling blacks and whites, probably unemployed, else hired to camouflage a Hi-tech War Machine, or retained to freeze an image of the Unreconstructed South.

The soldiers clambered into buses, colored olive-drab, of course, like the total Army down to the soil upon which it dwelt, and were driven to a vast expanse of mud crisscrossed by roads, connecting rows of barracks of raw lumber painted white (so much for over-generalizing about the Army's color scheme), though some were not yet painted and others were windowless and some were still only slabs of concrete. A glum sky glowered, damp, cold -- a treasure trove of bronchitis.

They tramped hither and yon, chilly above, muddy below the knees, dropping off contingents randomly. Then suddenly you arrived home: "From here on down the line, this is your barracks. Take your Bag and go on in and find a bunk." Typical of 100,000 across the Nation, the barracks might be of one or two stories, with entrances front and back, stoops as well, for they were lifted to air their bottoms above the elements, well-windowed; inside two rows of beds were footed upon a center aisle running the length of the building; at the front end you passed a large washroom where everyone might shower, shave and shit together. A man steeled himself each morning against finding his name on the list of latrine orderlies, or, missing this assignment, on the list of kitchen police, the next worst job. A small room housed the sergeant in charge.

They went out again and over to supply sheds where additional items of clothing and equipment were checked out to them. Some rookies had recovered from their trauma of indignities to a point where they actually could complain, but rude laughs would rebut any suggestion of changing a grotesque fit. Every last item on your list, the recruits were warned, possessed such great value that its loss would occasion, if not severe company punishment, then a deduction from your pay check that would keep you penniless into the distant future. As for selling as much as a pair of socks, a Court Martial and bitter lingering death in the guardhouse were foretold. From now on, one must forego even civilian underwear in favor of the General Issue. They were G.I.'s, wouldn't you know?

There was a prescribed place for everything that one owned or was allocated, a shelf on the wall above the head of the bed, a barracks bag below the bed, and a foot locker standing at the foot of his bed. Civilian clothing was an obscenity and any remaining bits of it, uprooted during the first Inspection, had to be sent home with pleas to preserve them until Johnny came marching home.

"The Duration and Six Months" was the military confinement visited upon them by their elected representatives in Congress; everyone used the phrase. For our Recruit the phrase was prophetic. It opened up an awful chasm of time that yawned before him daily, as it would before all separated lovers. No sooner had he a bunk whereupon to sit and write, than he despatched to her a resentful letter:

My only darling,

You were very inconsiderate to take off on a pleasure trip the day I gave up my rights as a citizen, freeman, and happy lover. It was such a moment for a token gesture of attachment. As matters turned out, it didn't make much of a practical difference, since I couldn't get leave to see you, but the fact of your deliberate action was painful to me. I realize, however, that I am in no position to make demands and hereby renounce any expectations implied in past agreements. If I felt you were splurging your id because of our engagement, I would be very sorry for you and myself.

So much for a page as dismal as the weather here. The skies spit on us day after day, splattering red mud on our disconsolate, stooped forms and adding to the nostalgia of everyone in the camp. Camp Tyson is new, with all the evil connotations of the word. No books, no service club, no established routines in many cases, no communication with the outside world. Paris is the nearest town. For the cost of a bus trip one can get the variety a new kind of monotony affords. He can pay twice as much for a theater, gape at women, & pick up a girl at a price. He can walk on cement, see seniles, admire babies and jostle civilians.

For four weeks our battery is confined to post, going through a so-called stiff training period. After that, we can get week-end leaves. Chicago is too far for a one and a half-day leave and I won't be able to come to Chicago except on leave...

This was said on February 25. However, "back at the ranch," as they say, SHE had been writing HIM. Hardly had he sent off his letter when HERS caught up with HIM in his foul circumstances, telling him of her joyful weekend:

La Crosse, Wisconsin

Saturday nite

My darling -

This is the ski weekend you heard so much about -- and it's been so much fun so far that it makes me all the more sad that we can't share these simple (well - they are simple, next to bars, movies and the competitive labor market) joys together.

The weekend is really a lot more elaborate & weekend-ish than I had expected. For one thing, La Crosse is 400 miles from Chicago, compared to the place we went to last weekend, which was only 90. We left at 4 yesterday -- Friday afternoon on - joy, oh joy! -- the Burlington zephyr. I take back everything I said about the Western trains -- this one was the tops. We got here about 8 last night - ate & went to bed. There are 5 of us -, Bets, Swish her sister & 2 boys. Jim McElroy & Doug Carroll. They were really going alone 1st - being wonderful skiers - but we girls kind of homed in on them.

And guess what! The train went through Rockford. I felt like jumping off the train when I saw the barracks. Well, I know where I'll spend the succeeding weekends.

Today's skiing was swell. The hills are really lovely around here & the one that has the tow on it is just swell.

I hope this letter gets to you - considering I don't know your company or anything.

Darling, I hope you're well and relatively happy. It's sort of stupid for me to say a lot of comforting things - or issue enjoinders to be brave etc. - You don't need them and, in a way, I'm not in a position to say them. After all, I am a girl & unfortunately we still - & probably will have it very easy indeed. And, in a way, I feel guilty having a good time without you - altho I know you wouldn't have it so. I'll write more when I'm surer of your address & am less chilled. Just wanted to say hello.

Your loving Jill

But then the grim truth was realized by her: life was not to be so controllable, not with the Army in charge. She hastens to write:

Wednesday

9:30 nite

Darling -

I'm writing this in an awful hurry because I want it to get out tonite. I just spoke to Vic - been calling them all night - and found out where you are. I've really been awfully worried - well, maybe worried isn't the right word but I can't think of anything else to describe the awful hollow feeling inside me. When I heard you'd left Camp Grant Saturday I felt just awful. I would have never gone skiing had I known you would be taken away in such short notice. You yourself assured me that you'd be around Chicago for just weeks - and I had no reason to believe otherwise. So forgive me for my ill-timed trip (incidentally, I did tell you I would probably go).

I wrote you from La Crosse Saturday to Camp Grant but don't suppose you got it.

Not much new. Job same except they are threatening me with all kinds of reprisals if I'm late again.

Please, darling, write me as soon as you get this letter - well, after the day's maneuvers are done, anyway. I love you and miss you so much. Maybe if & when you're settled on the coast or somewhere, we can be together again.

And please, darling, believe me. I really think you're the only man in the world I'll ever love. No, I haven't been seeing other men - except at a distance. This just arises out of a deep inner conviction.

Hey - my birthday was yesterday. Remember?

All my love,

Jill

and I'm so glad you're here. For a while I actually thought they'd shipped you to Tokyo!

It might as well have been Tokyo to his mind. A reign of terror appeared to be underway, conducted by the Cadre of corporals and sergeants. The work day began in chilly pre-dawn darkness with a flurry of whistles, recorded blare of the bugle, and bright lights flicked on by their buck Sergeant with a cheery shout of, "Awright, men, drop your cocks and grab your socks!" This gem of poesy had been learned by Sergeant Fazio on his first hitch, back in times immemorial. A routine of rush-and-wait ensued until the dusk of evening. The work-week culminated in an tense inspection on Saturday morning, this itself prefaced by scarifying threats from the buck sergeant in charge of the floor, and the confinement of half the soldiers to Camp for the weekend.

Much of the remaining time was spent waiting with muttered complaint for one thing or another -- the distribution of an article; assistance rendered the least competent, least willing, or most stupid; movement from one spot to another; hashing names in roll-calls; trivial announcements; and threats of punishment for offenses unimaginably numerous. Probably it was well, if unintended, that every soldier begin military life viewing candidly the human make-up with which the Struggle for the World would have to be won. It forbad illusions.

The Army proceeded on the theory that all needs were uniform and that all could be uniformly met, that all exceptions were violations of the rule of uniformity. The fountainhead of uniformity was close-order drill. Thence flowed a stream of rules for all behavior. Thus, "Men have been smoking in bed. This practice is forbidden at any and all times, under all circumstances. Offenders will be punished. By order of the Commanding Officer."... "Slippers and sport shoes will not be exposed under the bed. They may be stored neatly in foot-locker. By order of the Commanding Officer." There were rules for lining up outside the door of the mess hall, for placing yourself at table, for eating, clearing the tables, scraping your dishes, and leaving the dining room.

There was passed along a pasticcio of barracks wisdom, which sat atop the formal rules, telling you, for instance, that the buck sergeant (3 stripes) was the most important man in the Army, the First Sergeant the most powerful man. Also, "Don't volunteer for anything."..."Do bunk fatigue (rest on your bunk) whenever you can." The men added their own rules, whether of mealtime or in general, and one doesn't know when and where they originated -- in a silly peaceful Army of the remote past, it would seem. And "when a pitcher of milk or bowl of food is being passed along the table because someone asked for it, don't short-stop it!" And, " whoever takes the last portion of food from a bowl or the last of the liquid from a pitcher must get up and return to the kitchen counter for more (near the end of the meal he can ask if anybody wants any more and, if not, then take it and is not required to go up.)"

Our Hero found that he could always eat until his belly was stuffed. The food appeared ample, varied and nourishing. But, in fact, the Army managed at its peak of culinary incompetence to serve thirty million bad meals a day. Most of the vitamins had been killed by excessive watery cooking (after which the water was poured down the drain), by peeling them off (with knives that, in inept hands, cut off the best parts of whatever they sliced into), or by burning (by ultra-hot frying). The lard, greasy fried bacon, fat beef and pork, eggs, ice cream, butter, milk, and thick pastries guaranteed an abundance of harmful cholesterol and a wave of post-war heart disease. Renowned for serving pork and beans since time immemorial, the Army surprised our Recruit by offering them only occasionally. (For, it was literally true: "Nothing is too good for our boys," as the Great Guilty Civilian Conscience continuously exclaimed, but, a]. they didn't know what was good for the boys, and b]. the boys contributed to the ruin of the good.) Peas and other standard vegetables came in great cans. It felt strange, as looking through giant lenses at the world, to see the familiar labels from childhood (Del Monte, Campbell's) now grown gigantic on monster tins. Fruits came swimming in sugar-water, canned.

A vegetarian meal would have caused mutiny and therefore was impossible; a vegetarian would have been regarded as un-American, like a pacifist or a homosexual. Fish were safe from the U.S. Army. Catholics were assured by their chauvinistic priests that eating meat on Friday could be deemed patriotic, a sacrifice canceling a sacrifice. Kosher food was under similar stricture, with the connivance of bellicose rabbis in khaki. Priests, rabbis, ministers, and pastors -- all enjoyed the uniform and privileges of an officer but were supposed to mix with the enlisted men in ways that officers were discouraged from employing; they were voluntary commissars of morale. They ate with the officers and slept God knows where.

To make up for the mineral and vitamin deficiencies of his regular diet, a man could spend his meager pay on more pastries, chewing gum, ice cream, soda pop, and cookies at the Post Exchange and could buy a kind of beer that, despite its 3.2% alcoholic limit, put many a soldier on his way to the guardhouse, drunk. Some of the smarter men wondered how this could be possible; our Recruit, highly educated, ascribed it to psychosomatic effects, the beverage being an excuse for venting one's misery. The Chief, largest of the several Indians in his Battery and the most silent, and therefore called "Chief," could get drunk on anything purporting to be alcoholic, down to one part in a hundred. He preferred whiskey, however, and roamed the premises and beyond the gates melancholy in search of it.

The Mess Sergeant and Cook, also a sergeant, had gone to Army schools that taught them the names of utensils, instructed them how to handle bulky metal equipment, and set them free upon a company of men whose own taste was hardly developed enough to complain about any diet that gave them large amounts of beef and potatoes, along with gobs of real butter and lots of fresh milk. Coffee, too, with evaporated canned milk and spoonfuls of pure refined white sugar. There was, if you must know, an ideology behind it all: "Anybody who knows good food is a sissy," and probably un-American.

Our Recruit was one of the few who complained, his flanks protected by pals and proto-gourmets so that he could not be set upon as odd or picky; anyhow, it was commonly agreed that the food was tasteless and badly prepared. Whatever his opinion, our Boy was a chow-hound: "It tastes like horse manure, but it's good!" If not usually among the first in, he was ordinarily with the last to go out; he enjoyed sitting around with his buddies, talking, and watching the KPs come closer and closer, cleaning up, and then they went out for a smoke.

The cigarette habit afflicted a sizeable majority. Yet butts were rarely to be detected: discarding a butt occasioned a penalty; an unassignable butt might drive the proximate troop of soldiers into a long line to traverse the area, on the command, "Pick up Butts, Forward March!" Where cans were missing, butts could be toted in socks or pockets or carefully picked apart until they disappeared as dust (no one smoked filter cigarettes). Our Boy smoked Lucky Strikes whose "Lucky Strike Green Has Gone to War", according to the ads; there had been a valuable ink on the pack before it turned white. (By now you wouldn't draw a breath without claiming it to be part of the War Effort.) He smoked a cigarette after breakfast, one during the mid-morning break, one after dinner, then one in an afternoon break, one before supper, and a couple after supper, or more if gambling or hanging around the PX; it added up to less than half the typical man's smoking; yet perhaps a fourth of his barracks did not smoke at all. About half drank no alcohol. Marihuana, cocaine, heroin, and other drugs were not seen and hardly discussed.

Within a couple of days of arrival, you could begin to feel, well, these are the men of my company, which you learned quickly to call your "Battery." You were now, it appeared, in the Coast Artillery. It was useless to ask, "Why, then, is Camp Tyson so far from any coast?" This was basic training and basic it was. It consisted of basic hygiene, housekeeping, close order drill, cleaning and polishing shoes and buckles, saluting ("military courtesy" the recipients of the courtesy called it, just more "chicken shit" to the rank and file), handling and firing Enfield single-shot rifles from World War I, gesturing with fixed bayonets (What a lovely silly game: "Fix bayonets! Charge!"), clearing and setting tables and putting out food and washing pots and pans (the KPs were occasionally too liberal with the strong yellow bar-soap that was used for every purpose, so that the latrine would become busy in the middle of the night, with half of Battery A diarrhoeic with "the G.I's").

Only serious cases went to the hospital; the Recruit went once with the flu and 104 degrees of fever. At first roll-call you responded to the command, "Sick Call, Fall Out!", and assembled near the battery Headquarters, leered at suspiciously as a malingerer by the Corporal who was Charge of Quarters, and, after standing out in the cold morning awaiting a truck, while the rest of the battery marched off, were transported to the complex of long wood hospital barracks, there assigned a bed and issued the white gown of a patient. Your clothes were put under lock and key against any attempt at escaping the premises improperly discharged.

You were examined once a day by a doctor, with occasional readings of your temperature by a medic, and rarely you would spot a nurse dodging about. Only cough medicines and aspirin were doled out, laxatives and nose drops if needed. Penicillin was somewhere in the future. The main point was to get you out of the way of the Battery and near such therapeutic facilities as might be employed if your illness approached the terminal stage.

In a day Our Man felt well enough to join a poker game laid out on an empty bed and enjoyed passing the time that way, though a kibitzer, a jolly rotund pyknic type whose twinkling blue eyes concealed malice and envy, managed, by several sarcastic remarks, none of them intelligible except by inflection and direction at Our Man, to get under his skin, so he stopped playing the game at one point, leaned toward him with a mean look and told him to shut up or else, which situation let another player, a dark saturnine type, say to Our Man sympathetically, "Let it go," so he let it pass and the snotty fatso shut up. A trivial yet sole hostile confrontation, indicating the low order of personal violence in the Army then, while the films and pulp novels depicted brutal fisticuffs as the order of the day.

There was a chance for a little reading, there, too, but the ambiance was not designed to make men happy away from home. He missed his friends and the stupid training games, and was glad to be released and walk back to his barrack, feeling quite like a child with permission to go to school at midmorning when all was quiet on the streets. His barrack: that looked like them all, yet already, after a mere month, embraced his closest friends. And they did seem pleased enough to have him back.

It happened now that a notice was pinned upon the Battery Bulletin Board stating "Men with any previous military training leave their names with CQ." That would be people like myself, he thought, recalling the Black Horse Troop and the close-order drill and so on and musing that he might be able to help train some of the more inept stumblebums of the battery. Perhaps that was the idea; if so, though he put down his name, he never heard more of it.

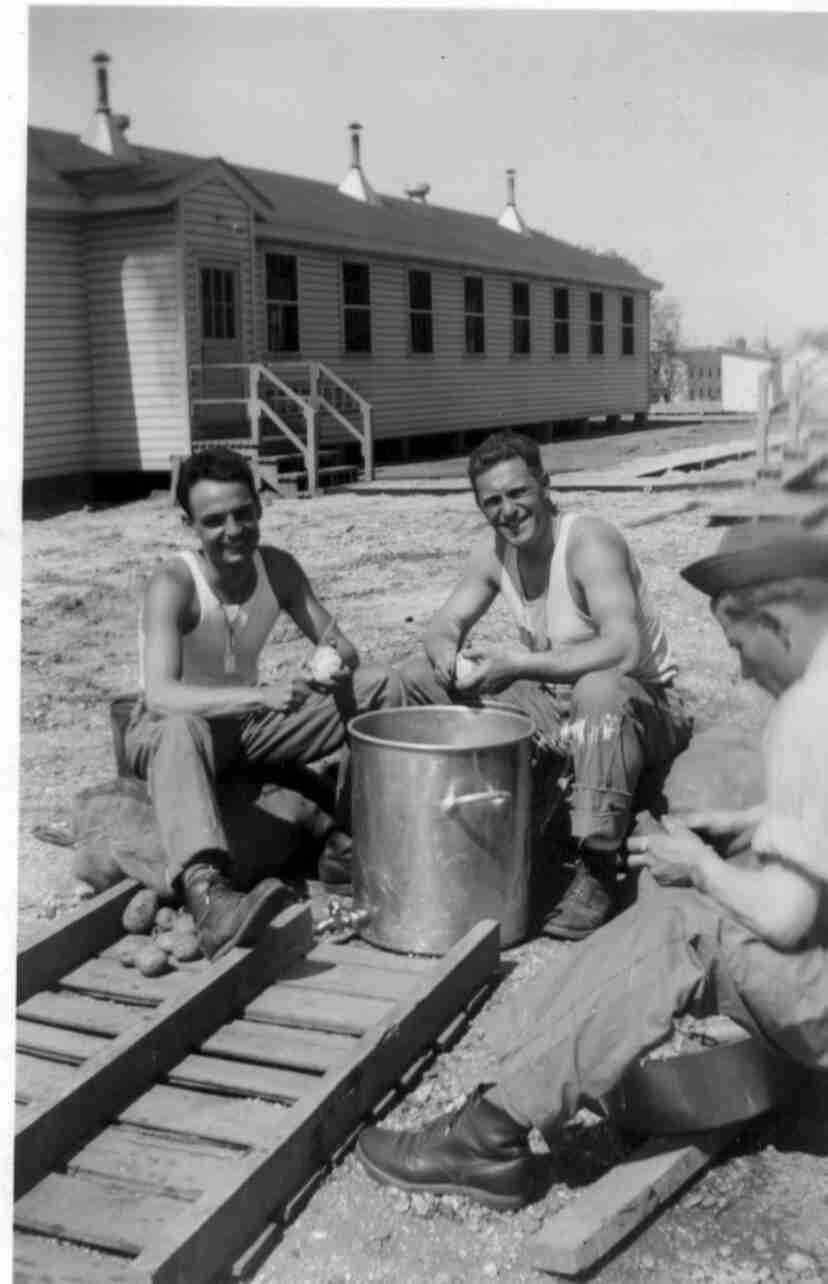

Instead he found his name repeatedly on the list of KP's for the day. Once every twenty-one days is OK, with perhaps one or two extra days for violating a rule, or returning after taps to the barrack, or arguing an order, or dragging your feet at an exercise, etc. None of this had happened. Still, day after day, he found his name posted on the list. After a couple of days of this, he realized that they wanted to teach a pretentious guy a lesson; theoretically, they might also have had the bright idea of keeping the least experienced men actively at drill, but this would have excessively taxed the brains of these regular army types, Our Man figured, and a couple of friends agreed.

He was aroused at 4:30, worked until 13:30, was off for two hours, and worked until 9 PM or 21:00 hours. (All Army documents were couched in the 24-hour idiom, but the soldiers, stubborn mules that they were, never would speak except in terms of the 12-hour rounds of the clock.) Brutal, unjust, fatiguing, stupid, yes: still there is no job in the world from which something constructive cannot be made. He knew what the menus were, ahead of time, and would tell the ever-hungry troops about their next meal; he could help himself to enticing tid-bits -- words too delicate for the pound slice of apple pie

and double dipper of ice cream taken in mid-afternoon. He became a guide like Virgil in Hell to the incoming Kitchen Police, introducing them to the horrors and warning them of the menaces thereabouts. He learned what was at the bottom of Army cookery, however gruesome the truth.

He watched with awe the process of fabricating the famous Army dish, "Creamed Chip Beef on Toast," so often served for breakfast, or whenever the Mess Sergeant was in a poor mood. You put hundreds of slices of white pre-sliced bread into the ovens until toasted. You meanwhile fill great aluminum pots with water. You pour large sacks of pure refined white flour into a large pot and stir in water until you have a uniform thick paste. You mix batches of paste with the pots of water to a satisfactory consistency, and bring them all up to a boil. You open a huge sack of shavings of dried beef, highly salted and anointed with dubious chemicals. You allocate quotas of this to the several pots and simmer them all. You place the toast on the tables, still slightly warm, with pitchers of the hot sauce. You let in the men. The men pour the treacle over the toast: voilá, "Shit on a Shingle!" It is a comforting way to begin the day.

The exercise paraphernalia was impressive: huge pots that one could almost crawl into, great trays of flatware, frying pans large enough for a pas de deux. Exhausting but healthful. Better, actually than what the other guys were doing, dressed in funny cotton blue fatigue uniforms for hard work, but mostly sitting around bored and dully listening, while a practical illiterate explained, time and time again, the handling of gas cylinders for a balloon or the care of your equipment, the limits to be imposed on your pathetic collection of toiletries and personalia, how to make your uniform last forever, the making up of one's bed. "There is only one way to do a thing: the Army Way!," or "There's the Army way and the Wrong Way!" which became corrupted to "There's the Army Way and the Right Way!", and only finally was something said about guns, the end-all of the game, or so our Recruit believed.

After dull hours of throwing oneself into position from which one was supposed to be able to fire accurately at an enemy approaching in a line like the British troops at the Battle of New Orleans -- on the ground and elbows, pointing; on your knees; on your feet. "Imagine you're holding a gun," they were commanded. The great day came when everyone was given a gun without ammunition, trained to carry it this way and that way, and finally marched to the butts where everyone was allowed to fire a few shots and qualify as marksman, which our Recruit did because by then he was back under arms, so to speak.

For, one day in the afternoon of his KP stint, aroused by the spring air and the drying of the mud, he walked out and down a lonely path on the outskirts of the camp, not feeling especially morose, and encountered a new First Lieutenant from his Battery. He was a ROTC man it was said, Lt. Lesser, a dark guy about his size, decent look about him. After an exchange of salutes, he asked the Recruit why he was walking around alone -- "you must have a personal problem," -- but the answer came as, no, really, just walking around thinking of this and that (wondering now, maybe it was the other who was lonely, or perhaps homosexual.)

So they walked along and exchanged questions and answers about schools and the war, and it occurred to the Recruit that he might mention being on permanent KP and he did so wonder about it out loud. (Enlisted men quickly learned not to carry a complaint or suggestion directly to an officer, indeed, not to speak to an officer, much less strike up a friendship with one; the two of them here, standing on the sunlit path far from the others, from the Army, speaking of the rules, seemed almost ipso facto to be breaking rules.)

The Lieutenant thought that something must be wrong and said he would look into it. They went their ways and the Lieutenant was as good as his word. The Recruit's name disappeared from the KP roster for quite a while. He was on hand, therefore, for the great day of maneuvers about which we shall quote a few words from a letter to Jill:

The briars and thorns..They were camouflaged and deceiving. They were tough as nails. And they were as numerous as the sands of time. I dived, time after time, into them and fear and hate them worse than barb-wire. My hands were bleeding in a dozen places and my friend Jester's nose had a vicious cut from one of the monster varieties. He wriggled around and yelled `De Grazia! I'm beginning to see red,' and I yelled back, `Stick it in the mouth of your canteen.' And we resumed firing. The attack had just started.. To my left was Tommaso, a tough little guy and a boy from N.Y.C. they call `Junior' for obvious reasons. Well, Jr. wandered into my territory and fell in the gully. So Tomas hollered out, `Hold Everything! Hold 'er up, someone's bin hurt!' I laughed so hard...

Some men liked maneuvers; they were a relief from the balloon drills and the sedentary aspects of training. Some were even imaginative and got into the spirit of battle, at least so long as real bullets and shells were not coming their way: such was Our Hero.

At night he does guard duty:

A guard post is a personal thing after the first hour. I know when I pass the great rustling tree hereafter I'll think of us playing on the beaches of California, because the noise was that of the sea. In the background of that whole stream of consciousness during the black watch from two to four A.M. was the measured clump of my shoes which persists like a metronome in the recollection. A sentry's night is a funny thing, mostly confused impressions on a dulled mind. A grunt, mumble, and squeaking of springs when the second relief is wakened in the middle of the night. Then a stumbling for the door, a second of attentive bodies, a "right face", and off to relieve the old guard. The new & old meet, a greeting is muttered, cartridges are transferred from one rifle to the other and you are left alone. What did the other sentry say? Something like "I've been walking guard with a big, black snake." Pleasant thought!

On my second slow round I see my companion. He is slithering along ahead of me. I have half a mind to let him be, any company being something, when two tippling bucks come along & I challenge them. "Pass," I say, "and watch out for the snake." Their sodden eyes see a huge serpent and after a furious battle of stones and words, crush the demon and walk away, arm in arm.

"Nobody loves a snake," I thought. "A worm, yes, but not a snake."

My shadow seemed like a snake, thirty feet of legs and rifle. With the natural persistence that makes it just to call love an obsession, I think of you and wonder if you're sleeping well. Just as I pass, and greet the neighboring sentry, the relief marches into view. I eject my cartridges. "Nice night" I say to my relief. "There's a dead snake in the road; don't mind him." He stirs and laughs a little and begins to walk. I feel very happy, light a cigarette, and head for my bunk.

She replied in her very next letter that she liked snakes, "I really do," and regretted its passing. Typically, their letters worked hand in glove, hers only several days apart from his. If she wrote that she was reading War and Peace and the short stories of Thomas Mann, he would hasten to reply that he was reading William Saroyan's My Name is Aram, and launch into an essay on humor, identifying him with S.J.Perelman. He adds a review of Rene Chambrun's I Saw France Fall, dismissing it as a "book of ex post facto predictions," by a "bourgeois lawyer of Paris. Ghastly analysis! Blames the Popular Front without any first-hand reason. Repeats capitalist slogan thinking. Account of Battle of France and the Maginot Line interesting and not too grim for the tea room." And he announces: "Coming soon: Review of Dragon's Teeth, by Upton Sinclair. The Chicago Tribune and News, Time and Life magazines, politics on all levels, cats, dogs, little brothers, the strategy of war, jobs at Esquire magazine, at Montgomery Ward's Department Store, bicycles and their use and maintenance, all the details of existence in camp and city burgeon from this interminable correspondence of wartime. Her epistolary world is Dickensian, with its multitude of characters of the Home Front candidly portrayed; her style is slash and burn, snap and crackle. Her morale is heartening:

I can't say too often how proud I am that you're in the Army. Perhaps it is a smug pride -- after all, it's you who have to suffer the discomforts and ennui of Army life. I wish I could, too, just to keep things even. I get awfully mad at all these punks, particularly around the University of Chicago, who are looking for a nice, safe desk job. John [John Hess, Tanks Corps EM, friend on furlough] and I ran into Stud [former object of her affections] at the U.T. last Thursday night, and he assured us that he was going to be able to stay out of the armed forces. It was pretty disgusting. And the ensigns -- most of them -- aren't much better.

And then he asked for and got from the Charge of Quarters, without the usual runaround and sneers, the rules for applying for officer training. Hank Dannenberg was all in favor of his trying for a commission. Such support was important: he wouldn't want the guys to feel that he put himself above them and wanted to desert them, nor did he in fact want to leave them. Life was a drag, but it was also a jolly shared mock-demanding pastime. Many a soldier refused officer candidature for just such reasons. The Recruit tried to get Hank and Johnny Chingos to apply with him, but they balked. His application papers did not go swimming through the channels of Camp Tyson. He is reporting to his beloved on May 15,

...I enquired about my application & was thoroughly enraged when I heard it was still dormant. I took over personally and, with application in hand, barged in upon office after office, shocking all Army standards of procedural propriety. I saw majors, captain, lieutenants and numerous sergeants with blunt requests for action. Our captain, poor soul, was perplexed no end by the irregularity. He was actually horrified to have my paper in the office and complained time after time that he couldn't understand how the papers were there. I ignored the asides. But lord, how they strained and squirmed to pass the buck on any number of details. Now it is completed...

He could not help but urge Hank again and again to apply. Hank had some ear trouble, an open ear drum from a boxing blow; it might block him; it might even cause an examining doctor to issue him a discharge, which would hurt Hank more than anything. The Recruit would have waived all such nonsense had he the right and power: Hank was magnificent as a leader of men, an organizer, an enthusiast, a warm guy full of sympathy for human problems, yet as tough as they come, a perfect soldier from the point of view of both non-coms and officers. He had been married and was in throes of divorce, not bothered by what must have been a lingering separation. He was in his middle thirties, 225 pounds of blonde hairy muscle, a professional boxer early on, a movie house manager for United Artists, one time with several theaters in hand, a dead ringer for movie star Kirk Douglas, had anyone known of Kirk Douglas yet. A bantam Boston Irishman confided in the Recruit from Chicago (a scholar if not a priest) that "He's the hardest working Jew I've ever seen." He meant, putting a compliment into his anti-semitism, that Hank could peel potatoes and dig ditches and send a balloon aloft better and faster than anyone in the Battery, always, too, in hearty good temper.

They formed a leading clique, had several guys who were close to them but none so close as themselves, Chester Dubois, Dominick Albano, Farley Reston, Johnny Chingos, who was the next strongest man in the company, and showed it one day when he came close to besting Hank in a rough and tumble wrestling match. But nobody would mix it with Chief, the towering Comanche who was the first man to be in and out of the guardhouse from the battery, for resisting arrest while drunk, and who could shoot a rifle better than anybody.

The village anti-named Paris was a gloomy setting for a Great Love. No lover in her right mind would voyage to these parts. That's why, shortly after arrival at Camp, you would grow an obsession that a calloused outside world had enveloped you in a murky time- freezing capsule. Nonetheless, in the numerous letters that they were writing to each other it became increasingly evident that a visit to Paris by her was in order and it had to be timed of a weekend when he could get a pass to leave the Camp, which would not be allowed until one's first six weeks had come and gone.

Then it did all jell: he managed to call her from the PX , she happened not to be in menstruation and managed to catch a train, and he managed to reserve a room in the tumbledown frame structure called the Paris Hotel. Down she came and they were delighted, he with her presence, she with the exotic barbarity of the setting. He took her to Camp and introduced her around, but much of the time they were engaged in sex relations, which had the aspect of coitus interruptus, because the room, as well as the hotel, cozied against the switching tracks and watering tank such that no sooner would they passionately embrace than a locomotive would chug, railroad cars would begin to clank and bum, men would shout, and the building would shake and tremble as if collapsing.

Jill went home and they wrote again and again and decided to get married if ever he could get to Chicago on a three-day pass. Thus:

Dearest love,

How is every little thing? Still love me? Cut out the comedy and give me a serious answer.

Because I'd hate to marry a girl this coming Sunday who didn't. I think this is it, darling. I've just spoken to the 1st Sergeant who is arranging a three-day pass (maybe four), starting Saturday at one. If all goes well, I'll be on the "City of Miami" at 10:30 that night and loving you to death shortly thereafter.

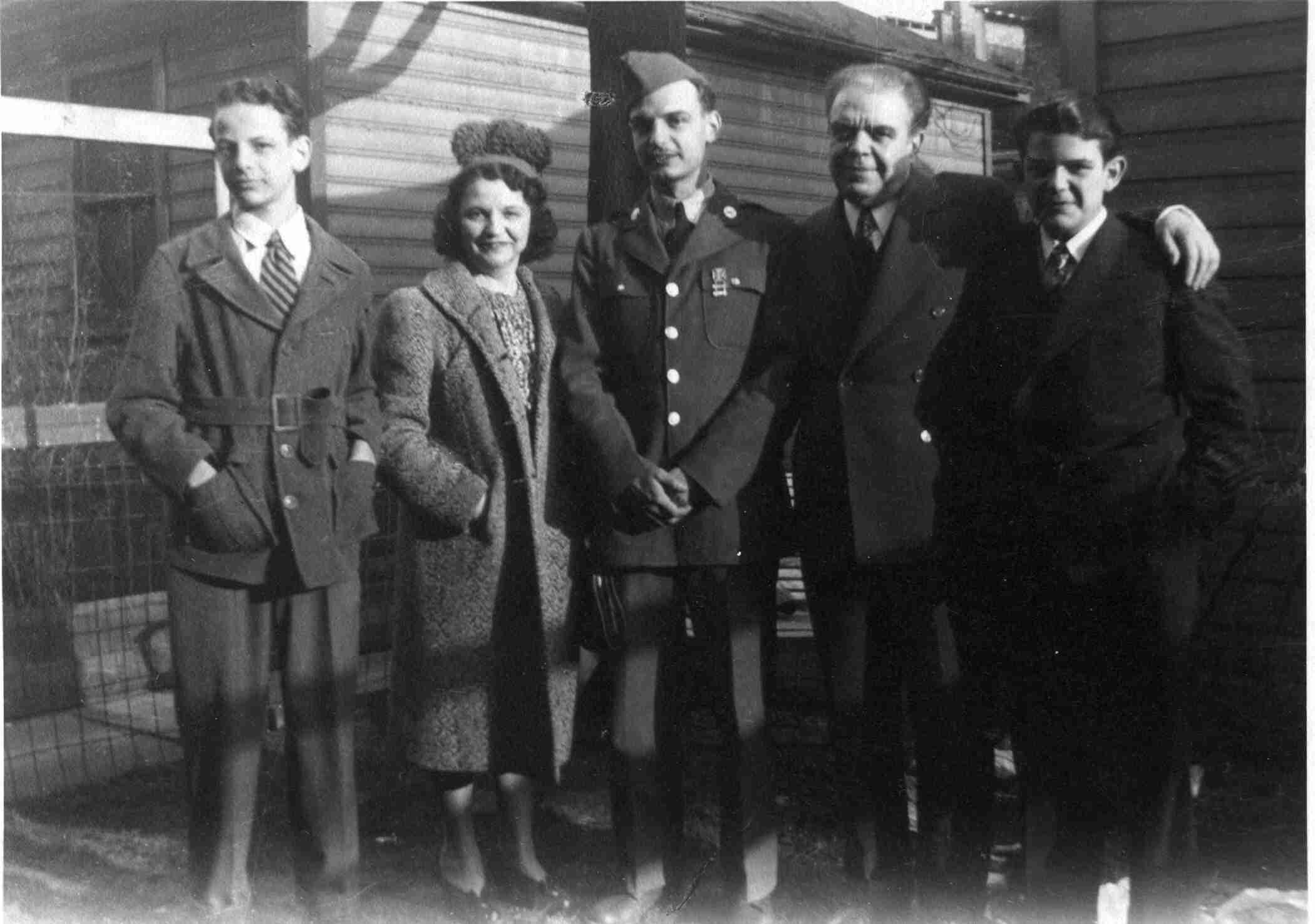

Hank Dannenberg will be with me on his way to NYC to get a divorce --funny? --. I'm sure you'll find him an eminently lovable character, enough so to be best man. To facilitate recognition, here is a picture of him, all 225 lbs. of brawn and as light as a mosquito.

The 302 is an old battalion, the first one here and they're a pleasant bunch. I'm giving a short current events lecture Wed. & Sat. at noon to the battery. I'm also rehearsing with the 306th dance orchestra. In other words, I have a few interesting things to do. But none so interesting as to keep me from longing & fretting for Saturday to come around.

I'll know for sure Wed. but am almost positive of the leave. Imagine yourself, if you can, as a married women, J.O., I can't quite. To me you'll always be someone I'm trying to make.

I've got to go, now. All my love and more. Will write right soon.

Your

Al

Love to all the family.

Thereupon they spoke on the telephone, a matter of his calling her from the PX, once he reached the head of the line at the booth. This and the other calls were not happy affairs. Too much was to be said, in too few minutes, with too much chance of saying the wrong thing.

My darling -

You deserve some explanation for my awful indecision tonight; yet I hardly know how to give you one. I have turned the moment that should have been our happiest into something miserable and confused for us both. Yet why I don't know.

Do I want to marry you? The question should be -- do you want to marry me, now? Al, I haven't changed. The things in me that made me undecided, quarrelsome, tearful before are still there. I yearn for things, the existence of which I can't define. I look frantically towards your love, and understanding, but I hardly know how to give you those things.

You grow furious with me when I call myself a neurotic -- it's a smug, pat generalization, I know - but I think I am. And then my anxieties are intensified because I think or know I am behaving differently from other people.

You want me -- and I'd like to, too -- go into marriage high- heartedly, viewing it as the climax of all my hopes and expectations. That's the way some girls -- maybe all -- do it. But how can I, Al? God, for two years now we've fought, equivocated, contemplated infidelity -- and loved -- one another. We must have had reasons for doing all those things. Or I must have had them (perhaps, truly, I was the sole instigator of all this atypical behavior).

And now I am on the verge of getting married, and worried sick because I don't have the same feelings I think other people have when they get married. Yes, I love you in my way -- that is -- I can't imagine loving anyone else. You are the fixed point in my existence. And because I realize that, I am afraid to get married. I have this idea that people get married for reasons that I don't understand -- not for my reason -- that I am lonely and dependent on you. Even when I say I love you, I sometimes feel that you and everyone else have a secret knowledge of the words that I don't and never will understand.

You see, I take my trouble to you as I have always taken it, telling you everything as if you were a detached observer. Which of course you're not, which must make this letter something at the same time ludicrous and painful to you. I want your assurance -- as if you were my mother! -- that no, I'm not the least bit queer or different from other people, that everything will be all right, that of course I should marry you. And, as I write these words, I do want to do that. But again, the pain rises up in me -- that I can never honestly be the sort of wife you need and want.

Shall I sum up what stands between us? It comprises all these vague yearnings, all this preoccupation with self -- the chief characteristics of my mildly disordered personality. When I see you again, I shall probably swear that I am whole and perfect as a government stamped side of beef. But there will be nights when I'll weep and toss and not know why --

When I see you -- and how much I want to -- I'll not be able to say the things I've said. I shall have forgotten them by then, because I never wanted to say them. By then, we'll either do what we both want to do -- I think -- or else we, or rather you, will make one more of your gentle accommodations. You've been wonderful to me, Al, all these years. [Actually only two: but it had been a heavy affair] You've really put up with a lot of -- well, the word is inappropriate in this context. But how much more can you take? I love you, darling, but God, do you really think you can stand being psycho-analyst, mother, brother and lover to me?

I'll get a room on the South Side for the weekend -- for Hank -- but how about us? I am staying here you know. Why don't we get the room & let him stay with your folks? They suggested he could.

And there were all these other things that came to my mind when you asked me tonight -- that I want to stay with my job because it's a good one, even tho all I have done is color counties red and blue. I was -- and am -- afraid that that's not the right attitude.

Please, darling, forgive me for all this crap.

Your

Jill

I sent your knife today. Watch for a small package from Field's. Hope you like it -- it was the most expensive one in the store.

Dearest love,

Wednesday

I should be used to hearing what you said over the phone, but somehow it hit me awfully hard last night, probably because I was so happy over the prospect of coming home.

Most certainly something must be done. I can't go on having you as a wife but not in name. It is terribly unfair to you. Whatever you say about being willing to go ahead, I can't let you do it.

For quite a while and perhaps even now, you thought me hard and untrustworthy. If that is why you don't want to marry me, I am happy -- first because neither is true and second because, if you believe it, it is something in me and not something in you. I pray that if we do not marry, it is because you think there are things about me you don't like. I pray that your reasons are not in yourself -- either because of not confiding in me something that stands in the way, something that has happened, or some basic disturbance in your character and mind. If this were so, I would be really smashed in heart and spirit.

All I care for in the world is that you be happy and well- adjusted. I could stand it being with someone else. I can't bear to have you torn within by something not rational, meaning by "rational" a weighing of my qualities against someone else's or yours. My stomach shrivels when I think that you may love me but that I can never make you happy.

I'm sending this letter before I receive yours because nothing will change what I've said. When I receive yours, I'll send either a telegram or another special delivery letter to you. I'll be home but can't say exactly when, - Sat. nite, I hope.

During all the time I've known you, I've never been unfaithful; the only exceptions you can recite me were done for the reason I told you, because I loved you so very much.

I seem to recall us being very happy together for months. In fact, it seems that when we were together we had delightful times, jaundiced over only by the uncertainty of their duration. But, again, I am not you and I may have been wrong. Perhaps you had happier times before then which you could recall & compare to my disadvantage.

I beg of you to tell me the truth about yourself. Put me in my place and I'll be content. You can count on me for all of your life for anything; so please don't feel that by leaving me you will be alone.

This is no love letter, darling, as you know. I'm not recounting the infinitude of pleasures you have given me and telling you how much I desire you. I don't want to sweep you into a marriage of reciprocal sympathy. I want you to love me as I love you, not with troubled feelings and deep insecurities, but with a lover's light heart and boundless acceptance.

If you decide to marry me, I will be most happy. If not, I want to know the true reasons why you don't.

I hope all this is not hurting your new work too much. But I know it is. Well, this love affair has hurt my work in the past, too, if that is any consolation.

Please smile for me, darling, and say, "Well, that ape wasn't for me but we had a lot of wonderful times together and we both came out the better for it." If not that, smile to think of Hank & myself staggering off the train with drunken grins and smile at the thought of our future marriage.

I love you,

Al

Darling -

I hope you'll forgive the awful paper and the scratchy pen but it's the best equipment I can find.

Your special came -- very belatedly (you should air mail a special to make it really effective) and I noted pictures with interest. Hank looks like Herb Blumer - or does he? - and appears to be a fine broth of a man. I shall fix him up with either Rosable - the racy type - or Marion Gerson - the pretty, sweet (but intelligent) type. Marion is somewhat shy and comes from a very sheltered background, but she's a damn nice girl, far and away the nicest I know, with the possible exception of Gertie Goldsmith. The only trouble is that she lives at the Ambassador, an inconvenient location.

Sweetheart, I'm awfully sorry about our phone conversation and the letter following it. In a way, I'm glad I wrote that letter. That is the way I feel basically, I guess. But I forget that I also feel other ways. While I think that essentially I am a confused and - for lack of a better word - apathetic personality, most of the time I behave and react as a normal happy person does. I think that, given the responsibility of a husband or a job, I can behave appropriately. I think I know how to act, even though my motivations to action are weak. (Please don't misunderstand me -- don't class yourself as a motivation and then get angry because you think I think you don't count ... I just mean that my most deep-seated wish is to retreat from everybody and everything, and sit in the sun. But as long as I don't do that - as long as I realize that there are things and people important enough to deny that wish -I guess I'll be all right).

If you're willing to take me this way, knowing that perhaps I am not entirely what a person should be - and I think my analysis of myself is correct as far as it goes - then let's get married. Certainly we can be happier together than we can singly.

But we can't get married Sunday. The license bureau isn't open. As that humorist in the County Building said when I called him, they're all in church -- and we should be too (he said). I can get my test Saturday & call for it Monday (takes 24 hours). Oh, & I can't get the license by myself because we both have to bring our certificates. So - if you still want to - let's get married Monday. I'll be able to take the day off if I tell them what for. I just hope I don't lose that lovely $40 a week job in the process of telling them. You can come to work Monday with me & then we can just walk across the hall & get the license. Hot dog! (Corny, ain't I?)

Monday night I dragged one suitcase down to the South Side to look for a place to live. I went to the Harvard Hotel and such places, & got so overwhelmingly disgusted I hopped right on the I.C. & went back to home & mother! Jesus, I've been spoiled by our apartment. And guess what! They didn't rent it after all. Apparently, the people who were going to take it welshed on the lease. Anyway, there was a big For Rent sign in the window when I biked by. (I left my bike with Jane Tallman, having no way to bring it to the North Side).

I'd like to take our apartment again. With the incentive of making a place for you to come home to, I really could fix it up nicely. (The incentive plus my income of $200 a month.) Your mother suggests that I wait upon your decision, wisely enough. Unless I hear otherwise from you, I'll delay the home business until you come home. As usual, I leave everything to you. But really, honey, the idea of a hotel room curdles my blood, & 5479 is so familiar to me that I wouldn't feel lonely in it while you were away. Not very lonely, anyway.

I ought to mail this now.

All my love,

Jill

"Why should I get married?" he asked himself repeatedly. There were many reasons why the marriage should fail; like the bumblebee, according to the laws of aerodynamics, ought not be able to fly. "But," so went his line of thought, "we're coming near to the end of the world in a certain sense, something so big is happening that to refrain from an action, otherwise quite reasonable and called for to cement the most important relationship of our young lives, would be cowardly. To cement it, to commemorate it, to celebrate it, would be fitting and proper."

So they did it. He hitched a ride to a town some distance away where the fast train from Miami paused and one could climb aboard. The train was full of bronzed slackers, big city slickers coming back from vacations in Florida, a hard-looking business crowd, both men and women, mostly Jewish, he noticed, with an embarrassment that they would not have felt, but his friends, the Oppenheims, the Gersons, the Hess's, would have, and old Hank would be fit to be tied. He was disgusted with them and hostile; "Not my kind of Jew," he thought. "Where was the war? In their pocketbooks. Where's the Promised Land? Miami! Damn, don't they know what the War is about?"

He came into Chicago, it was Saturday morning, and they were to stay with the folks on Addison Street. Jill and he went downtown to get a marriage license and learned that they needed a blood test, so they had to find a doctor who would testify they were free of venereal disease, which this one, caught emerging from his office, granted could be deduced from the man being a soldier with a recent Wassermann test on his card and the girl looking too neat and prim to be down with the clap.

The Mom and Dad later joined them as witnesses, Hank having flown the coop, and they went over to the City Hall, where the problem now turned into a search for someone with the authority to conduct a civil marriage. Found: one heavy-set bespectacled dark- jowled Slavic type from the County Clerk's Office, who could perform the ceremony without a tremor of emotion, and free them after a few minutes to go out with the folks for a cup of coffee. Then home. He showed up late for roll-call on Tuesday, but the CQ covered up for him.

There was not to be an end to jealousy on his side nor of lust. His large concession to fidelity was "not to go out of my way to look for women" and, when he did encounter an attractive female, he prided himself on playing with the lowest cards in the deck -- no squandering of money or resources, no lying about his marital status, no promises, no dressing "fit to kill", no interference with his higher calling, whatever that would be. He did have a need to experience women, or, as they said in humbler quarters, he was not ready to settle down yet. Womanless, in the presence of mixed singles, he could not but compete, for that, too, sexual competition, was part of his make-up. Still he was in love as he had been for years, unceasingly unfailingly ready to sacrifice anyone else for her, thinking practically of her alone as the object of love and sex.

It was before his marriage, for instance, that a dance orchestra came in from Paducah, Kentucky, with singers and dancers, and a beautiful girl danced; he cut around and through everybody with boldness and aplomb until he was alone with her, and had her dancing and scribbling down her name and address in Paducah; the Camp Tyson newspaper gossiped about his encounter with the hottest thing seen thereabouts since the Balloon went up in flames. He actually hitched there one fine Saturday, and inquired the whereabouts of her house at a barber shop nearby. On the one hand it was simply to ask for an address; on the other hand, it was a prudent bit of reconnaissance and intelligence, because he heard that she was married, that her husband was jealous, and that "folks heah ain't partial to soldiers cumin roun fixin to make trouble and gittin too friendly with the girls." So he wandered off after the butterflies of the pleasant Dixie Spring day.

And there was a strange moment on his first trip to Chicago, when he took a slow train and at this town where the train stopped, it was Galena, Illinois, he had time to kill and was in a hotel that had a balcony running around its foyer, where a beautiful woman took up a conversation -- she seemed to be with a party, for there had been two men talking with her. Suddenly she threw her arms around him and kissed him passionately and he was entranced, wondering what would happen next, when she pulled away as from a lover in an Italian Opera, sighing and throwing him kisses, and went tripping off down the stairs and out and he wiped off the lipstick and walked around some more and concluded that he could make nothing of the affair. A contribution to the War Effort, perhaps?

Nothing else, then, except the movies. He saw one a week at the Camp theater, one worse than another. The War Effort virus was infecting them more and more. And taking their dimes. He was paid $21 per month. Every dime counted. Yet at the same time money counted for little. You received your pay in cash, at an impressive ceremony, as elaborate as a marriage, in the Battery Dayroom, where you stood in line, in alphabetic order, and, advancing slowly but surely, ultimately arrived at the table where sat the Battery Clerk, the First Sergeant, and the Battery Finance Officer (normally an ordinary lieutenant charged with this detail), saluted briskly, received what was owed you, saluted again, executed what you hoped would be a respectable about-face, and retired.

Not $21 by any means, because deductions were removed beforehand: $6.60 for life insurance, to be paid to his parents upon his death, later changed over to his wife, several dollars toward the purchase of a Victory Bond, and the like. If a piece of equipment had been lost or deliberately or negligently broken, its cost would be deducted, as also a fine from a Court Martial. From the remainder, you would buy soap, lotions, beer, movie tickets, any article of clothing above the army's basic issue.

He was content with maximizing the army's hold on his property and was fully the G.I., in olive-drab from head to toe, inside and outside, heavy high shoes of leather with rubber soles, woolen socks, long-john khaki underwear, etc. with an olive-drab shirt, ill-fitting trousers and jacket with brass buttons, one horse-blanket overcoat, one overseas cap, two pairs of fatigues -- the overalls issued for everyday wear, two khaki handkerchiefs, and a belt of canvas with a brass buckle. That was all. When he needed a piece replaced, he would turn it in upon the appointed hour to the Supply Sergeant, who of course had a Supply Corporal, and this one would issue him a new item, asking him to sign for it, or send him off to the central depot if the Battery inventory had a shortfall.

There were guys who had a little money and felt a little freer and more elegant if they bought the few articles authorized for purchase, whether at the PX or at the army and navy stores that sold official gear in the towns of the country. The men could wear watches and did so, if they could afford them. The Army issued watches as the need arose, and to the appropriate grades -- not to ordinary dogfaces! Any private travel was, of course, paid for out of pocket. Cigarettes cost little, a nickel a pack at the PX, by the carton. A great many men could never had afforded cigarettes, given the tax and profit on them, were they still civilians; even now they would often buy tobacco in bulk to roll in papers or stuff in pipes; there were men who chewed tobacco, but it was going out of style, no spitting in the barracks.

You could barely scrape through the month if you wanted to go out for a night of beer drinking or whiskey, or buy a gift to send to someone out there, or buy books, newspapers and magazines, or eau de cologne, or chew too much gum, or have your woolens dry- cleaned. He washed his own stuff at the line of sinks in the large Barrack washroom; the Army didn't care if you were well-pressed so long as you were clean and it did a good job of cleaning up Battery A personnel within a couple of weeks.

Once broke, you could rely upon your comrades. Bumming cigarettes was epidemic as the month drew to an end. There would have arisen regularly a complicated network of indebtedness to be largely resolved in the hour following pay-call. The creditors skulked about the Battery Dayroom like wolves, letting no debtor escape. Gambling resulted in swift changes of fortune. Our Lad was a good gambler at dice, for reasons unknown. He could make them jump, bounce, careen, stop short, spin. Best of all, it seemed to him that with a scarcely detectable way of picking up the dice when his turn at dice came, and a way of palming them into the order in which he wanted them to fall, and a flat way of running them out over the blanket -- that with all this more often than chance the dice turned up his way. It is important that the gambler thinks that he is luckier than he really is in order to generate the volume of bets he needs to win heavily, but yet not believe he is so lucky as to bet foolishly.

He was helped in both regards by Hank, who played some himself but was not a hot gambler, whereas Our Private could work up a passion and enjoyed the orgasmic feeling of seeing the two faces of the dice reveal themselves like two lovers, but now and then as a rejection, or maybe only a momentary flirtatious turning of their behinds to you, so that you know surely on the next round you will set them down good and proper. And you do or you don't, while Hank held the money and collected for him one night when he began to beat the game, and Hank placed bets for himself as well. There you had it: the dozen players, the dozen watchers, the smoothed out khaki blanket, wooden slat floor, bare windows, naked bulb lighting the space, the squatters, the benders, the standers, the ever-moving bodies, all fascinated by the action. And the side bets. As he played he could hear the babble of voices:"1 to 3 he comes on the next roll, who'll take it?" "I got you!" "All faded? Let 'em roll!" "Come on, sweet 7!" "Come on, snake-eyes!" "Damn!" You sense who is with you and against you, who is thinking you must be hot and is beginning to ride on you.

You pray hard to make your point, you squeeze it out of your dice, but at the same time you are thinking what am I going to do when I make it, should I pinch the pot, take the winnings, retreat way back to where I started, or let it all ride, go for broke? The smoke rises thickly, the grunts and calls get louder, somebody shouts thinking you must be hot and betting for your point to come, 2 to 1, while the unbeliever sticks grimly, going his own way, and keeps betting 1 to 2 on a crap-out.

Then straightening up and stretching your limbs finally when it is time to go, perhaps for everyone, or for the broke ones, or for yourselves, whether you've lost as much as you can afford, or won as much as you think you can win this night, usually only a few bucks, oh, but there was that Great Night when Al was hot as a pistol and Hank was booming right alongside of him and they cleaned up the blanket with fifty bucks apiece, two and a half months' pay when a 29-cent stamp cost 2 cents and the nickel cigar and nickel beer prevailed. And friendship -- probably it has inflated even more.

All in all, "A" Battery was a friendly 300-man aggregate, where over several months there were no fisticuffs in anger -- so much for the idea that Americans, all the more when they were a melting pot of strangers, continually brawled. Their leaders -- the officers -- were practically unknown to them, and known only distantly to the non-commissioned officers who ran the company in proverbial army style. They were regular army, these non-coms; most had served as privates for years, their own old non-coms having been shipped into outfits going overseas or already there or retired from the army. You might say they were a lot of Hillbillies and Italians and End of the Road farm boys and onetime riffraff from the big cities. They were supremely ignorant and narrow, but comforting in the very ponderosity of their behavior and in their conviction that the army will take care of you, just don't cause trouble and keep your nose clean and do as you are told.

The recruits in themselves constituted an ethnic and geographical fantasy, the main elements coming from an Italian neighborhood of the West Side of Chicago, a Jewish neighborhood of Brooklyn, a scraping of Okies and of Indians caught off the reservation, remote Scandinavians of the northwest, and a dozen other types. Absent by the vagaries of assignment were Far-Westerners and Deep- Southerners. Blacks had been segregated, both here and everywhere; the Old Army had been racist and the Army would continue to discriminate invidiously until forced by the Federal Government and Liberal Opinion -- and perhaps by an anticipation of high casualties - - to integrate its troops racially.

Intellectuals were totally absent from all ranks up through the Post Commandant, so far as he could tell -- all except Prof. Ziegler of Amherst College's Political Science Department who came, hated it all, and went to who knows where. These two should have loved one another -- and indeed they did communicate in the academic mode and code on several occasions -- but Our Private was no longer, not socially, an intellectual; he liked the guys around him, and intellectually he lived off his fat, plus a few books, and the letters from his girl-friend.

A dark-skinned Oklahoman, perhaps carrying along with his "white" classification the genes of Cherokees and Blacks, as do a number from that country, a cheerful stocky farmhand, bunked next to Our Chicagoan in the big room of many beds. The Chicagoan had brought along with him from home a copy of Cohen and Nagel's formidable volume on An Introduction to Logic and Scientific Method that he had stolen from the University of Chicago Library. If anything could justify the period of Basic Training, he thought, it would be the mastery of this work. He left it laying upon his bunk one Saturday afternoon to toss a baseball outside, and when he returned a while later the Okie was reading it with interest. He handed it back promptly. "How did you like it?" "It's interesting," he said, "It's just like common sense." The Chicagoan could not make out whether the guy was disappointed that it was decipherable or pleased that he could handle it.

He had only an elementary school education. Hardly a man in the battery had been to junior college and many, including the non- coms, had not finished high school. They were not noticeably different from the Americans whom the Chicagoan had known, except from the academics and intellectuals, who are really the only distinct class in America or were until mass higher education and hi-tech industry swept over the country beginning in the fifties. In manners and considerateness, the men compared favorably with the business class of the American cities and the fraternity and athletic circles of the University.

With the gossip bruited about and his application for Officer's School before them, the officers could respond readily to national directives urging All Personnel to conduct orientation and education sessions for the troops. They were already viewing the war propaganda films that Frank Capra was directing from Hollywood on "The Nature of the Enemy." So on Wednesdays and Saturdays, in the mess-hall after lunch, he was on detail to lecture "A" battery, officers included, on the news and on the meaning of the war. He delivered discouraging news, reminding them that a Japanese submarine had fired upon Santa Barbara, California oil installations and the enemy had taken over the whole of the Western Pacific and Southeast Asia.

What he could not tell them, because such news was kept secret (a mistake in mobilizing the country), was that a month earlier all Allied shipping had been halted by losses too heavy to sustain, 834,164 tons or 273 ships; that the Battle of the Java Sea was a serious defeat; and, also because it was not "battle-relevant", the first trainload of Jews had been shipped out of Paris, France, destined to die at Auschwitz.

He then gave them encouraging news on the progress of the War, which they already had known but liked to hear from the podium -- that the Russians were holding fast, that American planes had successfully bombed Tokyo and other cities of Japan, and so on.

He would then scold them for being lazy and negligent citizens who had allowed the government to be isolationist, to divorce itself from world problems, and to allow the Fascists, Nazis, Imperialists of Japan and all of their minions in various other nations, including the USA, to grow enormously in power and influence, until the very minds and souls of people everywhere were being meanly controlled, along with their lives and fortunes. The enemy, having taken over their own countries, practically all of Europe and Asia, and even to be found in Alaska, Africa and battering at the doors of America and Australia, would soon target Detroit, Chicago, New York and Washington. So here we are, he expostulated, going to fight thousands of miles away because of inattention to the world around us.

He was half-baked, ill-prepared, arrogant, dogmatic, but his act went over well. Everyone felt better. Americans feel better if they've been lectured; it's as if they've gone to church and heard a sermon. It's true, of course, that he had enjoyed a certain experience as a teacher, had experienced hundreds of lectures of all types, knew the background of the War and devoured the news daily, so he could be confident, which in the last analysis is what the lecturer ought be, especially before troops, and put him well ahead of the audience; no one else, from the captain down to the "sad-sack" recruit out of the Ozarks, had any idea of how to conduct such affairs and even if he had done well would not have the self-confidence to judge his performance.

They might better appraise him as a Balloon Chief, for they had all started equally and totally ignorant with regard to balloons. Few had ever flown a kite. Now a number of them had qualified for ratings as corporals and sergeants and would be training others to fly the balloons. There would eventually be a million promotions in the Army of ten millions, even if the casualty rate should be low enough to put a brake on promotions. But then there were the nine millions who never reached beyond Private First Class.

Modest talk of ratings entranced the men as they sat upon the wooden stoops in the warm light of the Spring. To most of them a promotion to PFC, Corporal, or one of the several grades of Sergeant would have been a great leap forward. What couldn't be done with another twenty dollars a month! Soon they would get $45.00 per month, everyone would. What a great payday that was! It took many soldiers several months to raise their standard of living high enough to dispose of their surpluses.

It did not stop, however, the interminable argument of the barracks stoop as to what was the best grade to possess in the Army. Strangely, there floated an old myth that the best grade of all was the Warrant Officer! He was half officer, half top sergeant, got respect from all sides, appeared independent in consequence. No one had yet encountered one of the species save from a distance.

Argument proceeded, also, on the question, who made the best officers: Soldiers with battlefield promotions, men who had gone through Officer Candidates School, West Point graduates, Reserve Officer Training Corps products, or National Guard officers? The preponderance of opinion rated the five groups as West Pointers, first, then battlefield officers, then OCS, NG and ROTC. Considering the inexperience of the soldiers, the ordering was remarkably intelligent.

At first, unlike everyone else around, Our Man was disappointed in his assignment. He wanted to have something to do with high explosives. He felt consoled upon learning that these dragon-like creatures were to be filled with hydrogen gas, after their first trials with helium, because everybody knew that hydrogen was highly inflammable and explosive, whether mixed with oxygen or touched by flame. The greatest care had to be used in filling the balloons from the gas cylinders and afterwards in releasing the gas from the balloon when collapsing it for transportation and storage. One day the biggest balloon in camp nearly got away when a little convoy balloon tangled with it. They poised together in the air for a minute, "looking" he wrote, "like two lazy, copulating carp. Then a tear appeared in the big fellow and he was hauled down rapidly."

They heard that the balloons were being used in London and on ships at sea, and the idea of being sea sick repelled him -- he had been quite nauseated on a couple of trips across the Atlantic Ocean before the War began; he disliked, too, the sense of confinement he believed would be part of a marine existence, an idea that had discouraged him from applying to the Navy for a Commission when he might have done so. Furthermore, he believed in the ultimate supremacy of land-based power and that the United States, like the Soviet Union and Germany, was fundamentally bound to the land, unlike the British Empire. At any rate, he discovered a modicum of danger in these balloons and experienced with pleasure how they tugged like wild horses when you tried to launch them or moor them in a wind; he could picture how they might bring down or scare off a dive-bomber from a direct approach to his ship. Or, if they came at his boat crosswise, midships, they wouldn't be able to rake the ship well with their machine guns. It is remarkable how much of the time of the soldier, so little of which can be spent in combat, is occupied in violent fantasy. The soldier must therefore always be something of a child. Unless he blanks out, a dullard.

Privately, he did not become reconciled to the Barrage Balloon Corps and the chief reason was that he did not believe that they could have much to do with winning the War. He was set, heart and head, upon fulfilling some function that would be dangerous without being fatal and that was involved in the thrusts that would win the War. He did not see much future in the Coast Artillery for that matter and wondered and would continue to wonder why they did not shut it down, as it was becoming most unlikely that the Japanese or the Italians and Germans were going to come steaming up to our coastlines, blow up our cities, and land a mass of troops.

They were told, however, that it used to be the choicest combat arm, asking the most of the military brain to operate its long-range cannon, and affording the most luxurious life within its seaside garrisons. He could see none of this and even doubted it, for the Air Force was now the most technical branch. He had begun soon after arriving in Camp to plot a transfer to another arm. But meanwhile he had no alternative to entering the Coast Artillery's Officer School. They were seeking a great many new officers. The reason was soon made clear. The anti-aircraft function, the most technical type of artillery, had been given over to the Coast Artillery. And there were armadas of Axis aircraft doing great damage, which had to be shot down.

It appeared that he was qualified to direct such cannons, and he was called before an Examining Board to determine whether he was inordinately ugly, improperly garbed, of sagging morale and lacking self-confidence, badly informed, and wanting in the judgement expected of one to be entrusted with matters of life and death. The Board's two lieutenant-colonels and single major were pleasant beyond what one might reasonably expect, given the burden laying upon them. They chit-chatted easily and comfortably. How do you feel, asked one of the Colonels, probably not of German origin, about fighting the war against Italy, assuming, as it appeared from the Candidate's name, that he was of Italian descent. He replied that Italy had begun the war, that fascism was no good, Mussolini a dangerous dictator and that Italians as a whole were unenthusiastic about fighting, especially against Americans, but that a lot of them would have to be killed before they would be able to extricate themselves, and that he anticipated taking part in the action. It did occur to the Candidate, who had achieved a certain subtlety in such matters, that it would have been quite useless, or, as the Army people came later to say, counter-productive, to object to the stereotype that lay behind the question. Here was a war in which about a quarter of the American combatants were of German origin and about ten per cent were of Italian origin, not to mention all the other Americans descended all or in part from nationalities, like Croatians and Ukrainians and South Irish, who were engaged by sympathy or conduct upon the enemy's side. (The prejudiced follies that were being perpetrated against the Japanese-Americans of Hawaii and the West Coast were far from the consciousness of both Board and Candidate. Nor were questions being asked of the more important sources operating against the war effort, the anti-communist fanatics, the racists who insisted that blacks be kept segregated and not allowed into fighting units, and so on.) Actually it was evident that the Board expected no problem with the answer, expected, in fact, rip-roaring chauvinism.

The question that actually stumped the Candidate and embarrassed him later on when he recollected it, was logical, clear and relevant: "How much dirt can a man dig out in a day?" He stared bewildered at the Colonel, who after a moment almost apologized for his question, "Well, you know, he said, we have to be practical," and smiled kindly. Our Man smiled back and everyone smiled and he replied, "I am sorry, sir, I don't know but I believe that I ought to know." (Should he have said: "What sort of man, under what kind of conditions, working on what kind of ground?" and then admitted ignorance of that, too?) But it was the last remark of any consequence. He was elevated to the rank of Corporal, Candidate and Cadet.

Now it was a matter of waiting for the orders that would give him ten days of freedom in Chicago en route to Camp Davis, North Carolina, for at least three months in officer's training. He was by no means assured of winning a Commission, although he could hardly believe otherwise. Hank and the gang were sorry to part with him but looked forward to an Odyssean return, when he might exact salutes and demeaning details from the non-coms on their shit-list. The Candidate was less sanguine about this prospect, as well as more forgiving of disposition. He had heard, and it seemed reasonable, that precisely in order to avoid this kind of vengeful hazing, newly commissioned officers were not sent back to their former units or even their former camps. Besides, the social barriers between officers and enlisted men would in most cases put the newly commissioned officer ill at ease with his former buddies.

The American Army was growing too rapidly and moving people around too mechanically for attachments to endure. The Camps were all much alike; it could hardly matter where one was dumped. They were equipped now with recordings and loud-speakers that sounded the various calls of the day on a technically flawless bugle: reveille at dawn, assembly, mess-call ("soupy, soupy, soupy..), retreat and taps. Retreat was the favorite call, for it fell at the close of the day's work, and often as the sun went down, and the Stars and Stripes were lowered reverently from the flagpole: it is a call of peace and freedom. Too bad Retreat had to be sounded automatically, inhumanly. Hank and the others would even walk some distance toward the pole in order to freeze at attention and salute the flag as it descended.

A few bugles were still inventoried. One came to the hands of the new Corporal from Chicago. He could play it; he had been bugler at a Boy Scout Camp at Berrien Springs, Michigan, one time; and you will recall his trumpeting. A cluster of G.I's gathered around his bunk while he sounded off various calls, with verve or with nostalgia, as deserved. That's it! That's what we need, they exclaimed, a live bugle! It even occurred to them that he might play the bugle at Retreat in place of the recording. Go ahead! Yeah! Sure! You sound better than that tin horn! Why not! A delegation, with Hank in the lead, went over to the Military Police and proposed the idea. O.K. Just this once.

Like a gladiator with his trainers and sponsors, the Corporal walked to the flagpole the same afternoon, late, and stood by. As the Flag Detail loosened the rope, he sounded Retreat. He had a powerful open tone, he hardly needed the help of the amplifier. He sang out over the wooden barracks and Tennessee fields as if they stretched out from the Place de la Concorde. The soldiers stood around marvelling. THIS was the Army. Human! Caring! Friends! Peace! He blew beautifully; he didn't quite remember the second passage of the call; it is a complicated call; but he improvised well, elided nicely, Hank, who knew, said enthusiastically, you didn't get it exactly right, but it was wonderful.

He was surprised and happy at the shower of compliments afterwards coming from the cluster of men around the flagpole. They had stood as stiff as ramrods and saluted up and down as sharp as razors to lend his bugling moral support. It was the real-life restoration of the hoary tradition of the Army of the United States, Its Imperial Majesty, as they dreamed of it and saw it in the old movies. It gave the recruits one up on their Old Army cadre, too, because those men of yore, when the days went nowhere into the future but interminably into the Retreats of each sunset, and the freedom of the evening afterwards, were deeply stirred, and they too talked of the real live bugling of Retreat.

They made plans to perform Retreat this way at least once a week, maybe on Friday or Saturday. The Corporal was catching the right spirit; he resolved to get hold of the Army Manual for the Bugle and refresh his memory over the melody of the summons.