Looking back upon the jagged landscape of literary creation in America in the Twentieth Century, it strikes us that several of the peaks that still catch the light were under serious threat, in the name of "good taste" and "decency," and through the action of government itself, never to receive the light of day in the first place. Allen Ginsberg's Howl is one such peak. So is William S. Burroughs Naked Lunch. So are Nabokov's Lolita, Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer. So is the Irish Himalaya itself, Ulysses. Yet, before we shake our heads in disgust and disbelief, let's not lose sight of the fact that it was tools of the refashioned American Constitution that were the weapon that, in the hands of freedom-minded lawyers, judges, intellectuals and publishers, were able to fight the repressive forces of government and conservative pressure groups. Such a lawyer was Edward de Grazia, who was at the forefront from the fifties onward, leading the shock-troups of the freedom fighters. My - he even served as a lawyer for Aristophanes, when Lysistrata was banned in the days of the Vietnam War! He fought for Lenny Bruce. He fought for I'm Curious - Yellow. The abundant freedom of expression secured during these decades is due to the struggle of a relatively small number of people (not that they didn't have a large, silent support). To put the importance of this fight into perspective, we need only consider the deserts of creation left behind by totalitarian systems of the same period, where bureaucracy and ideological bigotry went unchecked by the champions of democratic law.

I met Allen Ginsberg in the fall of 1964 on the eve of the Boston trial of William Burroughs' Naked Lunch. Allen helped Burroughs write Naked Lunch and helped me to orchestrate the novel's defense in what Allen later described as "the dialogue we improvised together in the theater of a Boston courtroom."

That "dialogue" played a major role in freeing Naked Lunch, in particular, and artists, in general, from censorship.

After the trial we took a train back to New York together and became friends and allies in the movements to end the war in Vietnam and to expand freedom of literary and artistic expression in the United States.

ALLEN GINSBERG: We traveled South by overnight train thereafter and talked Law and Art. I met his circle of libertarian friends in Washington and followed his career as art and liberty-defending lawyer in cases involving Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer and the film I Am Curious-Yellow, and his adventures rescuing Norman Mailer and others from jail during anti-war peace protests and exorcisms at the Pentagon ( For a first-hand account of the Pentagon affair, see Norman Mailer's Armies of the Night.) in the late '60's ....

The Supreme Court in those years was wrestling with the problem of whether and how to make policemen and lower court judges leave sex alone in literature, art, and entertainment.

One of the few breaks in the 200-year-long Anglo-American judicial practice of censoring literature and art took place in 1959 - two years after the Supreme Court's landmark decision in Roth v. United States - when federal Judge Clayton Horn stopped San Francisco policemen from destroying all copies of Allen's poem Howl. In the process, Judge Horn also freed Howl publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti from criminal charges of selling an obscene book at his City Lights Books.

At the time, Allen was in Tangier with Jack Kerouac, helping Bill Burroughs put Naked Lunch into publishable shape. In San Francisco, Judge Horn allowed nine literary experts to testify about Howl, including Mark Schorer, Luther Nichols, Walter Van Tilburg Clark, Herbert Blau, Arthur Foff, Kenneth Rexroth, and Vincent McHugh. They addressed the literary merit of Ginsberg's work and, even more significantly, the poem's social importance. Howl was not "art for art's sake" but deep social criticism, a literary work that hurled charge after charge at the values of American society, just then trying to shake off the malaise of McCarthyism.

The prosecutor in the Howl case was Ralph McIntosh, whose earlier targets included nudist magazines and Howard Hughes' sensual Jane Russell movie The Outlaw. But Allen's poem took McIntosh beyond his depth. He could not understand the poem, except for the dirty words, and neither literary critic Mark Schorer, the defense's main witness, nor Judge Horn, who tried the case without a jury, would help him out.

RALPH McINTOSH: I presume you understand the whole thing, is that right?

MARK SCHORER: I hope so. It's not always easy to know that one understands exactly what a contemporary poet is saying ....

RALPH McINTOSH: Do you understand what "angel headed hipsters burning for the ancient connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night" means?

MARK SCHORER: Sir, you can't translate poetry into prose. That's why it's poetry.

RALPH McINTOSH: In other words, you don't have to understand the words.

MARK SCHORER: You don't understand the individual words taken out of their context. You can no more translate it back into logical prose English than you can say what a surrealistic painting means in words, because it's not prose ... I can't possibly translate, nor, I am sure, can anyone in this room translate the opening part of this into rational prose.

RALPH McINTOSH: Your Honor, frankly I have only got a batch of law degrees. I don't know anything about literature. But I would like to find out what this is all about. It's like this modern painting nowadays, surrealism or whatever they call it, where they have a monkey come in and do some finger painting.

When McIntosh tried to get Schorer to admit that some of the "obscene" terms Allen used could "have been worded some other way," Judge Horn intervened: "It is obvious that the author could have used another term but that's up to the author to decide." Judge Horn was not prepared to let policemen or prosecutors mess around with Allen's artistic freedom, nor to let an expert witness be browbeaten.

Other defense witnesses also racked up points on Allen's side:

LUTHER NICHOLS: The words he has used are valid and necessary, if he's to be honest with his purpose ...

WALTER VAN TILBURG CLARK: They seem to me, all of the poems in this volume Howl, to be the work of a thoroughly honest poet who is also a highly competent technician ...

KENNETH REXROTH: Its merit is extraordinarily high. It is probably the most remarkable single poem published by a young man since the second war.

Two rebuttal witnesses took the stand for the People of the State of California. One, an assistant professor of English at the University of San Francisco, David Kirk, said he thought Howl was a "poem dedicated to a long-dead movement called Dadaism." The other, Gail Potter - who said she had taught at a business college, a church school for girls, and the College of Southern Florida at Lakeland - said that in reading Howl she felt as though she were "going through the gutter." The prosecutor closed his case by asking the judge to consider whether he "would like to see this sort of poetry printed in your local newspaper" or "read to you over the radio as a diet."

"In other words, Your Honor," asked McIntosh, "How far are we going to license the use of filthy, vulgar, obscene, and disgusting language? How far can we go?"

Judge Horn was prepared to go as far, apparently, as Justice William J. Brennan's opinion in Roth would take him. Said Horn, glossing one of Justice Brennan's prouncements in Roth: "Unless the book is entirely I lacking in 'social importance' it cannot be held 'obscene."'

The judge had read Howl, listened to the defense witnesses, grasped what Allen was saying and recognized that the poem was a Howl of social protest and sexual and political dissent.

JUDGE CLAYTON W. HORN: The first part of Howl presents a picture of a nightmare world, the second part is an indictment of those elements in modern society destructive of the best qualities of human nature; such elements are predominantly identified as materialism, conformity, and mechanization leading toward war. The third part presents a picture of an individual who is a specific representation of what the author conceives as a general condition .... Footnote to Howl seems to be a declamation that everything in the world is holy, including parts of the body by name. It ends in a plea for holy living ...

Judge Horn regularly taught Bible class in Sunday school; perhaps he was reached by Allen's messianism. He found the poem full of "unorthodox and controversial ideas," which, although expressed at times through the use of "coarse and vulgar" words, were, nevertheless, meant to be protected by the constitutional freedoms of speech and press. And he believed that the First Amendment had been adopted to free just such "ideas" in Justice Brennan's terminology, "unorthodox ideas, controversial ideas, even ideas hateful to the prevailing climate of opinion." He recognized Allen's Howl as an outpouring of such ideas. That the poet used "obscene" or "indecent" words and images to convey those ideas did not destroy their entitlement to constitutional protection.

JUDGE CLAYTON W. HORN: The author of Howl has used those words because he believed that his portrayal required them as being in character. The People [of the State of California, represented by their attorney] state that it is not necessary to use such words and that others would be more palatable to good taste. The answer is that life is not encased in one formula whereby everyone acts the same or conforms to a particular pattern. No two persons think alike; we were all made from the same mold but in different patterns. Would there be any freedom of press or speech if one must reduce his vocabulary to vapid innocuous euphemisms? An author should be real in treating his subject and be allowed to express his thoughts and ideas in his own words ...

Thus was Howl freed from censorship to become one of this century's most important and influential poems and a worldwide best-seller. But the book Allen helped Bill Burroughs to write still had a trial of its own to face.

The problem in Boston with Naked Lunch arose because several of the book's savagely comic scenarios explore the hallucinatory potential of mixing sex, lethal violence, and drugs.

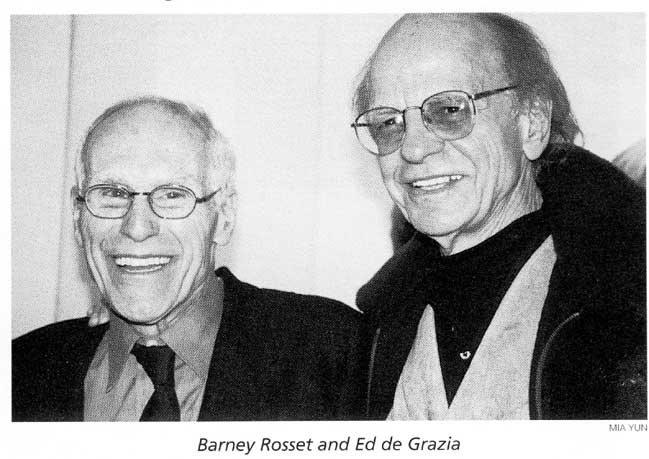

During the 1960s, Barney Rosset of Grove Press fame brought out many morally, politically, and sexually incorrect works of literature and art, including D.H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterly's Lover, Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer, Jean Genet's A Thiefs Journal, the "anonymous" Story of O, and the Swedish film 1 Am CuriousYellow, directed by Vilgot Sjoman, a protege of Ingmar Bergman. After reading Burroughs' unpublished manuscript, Henry Miller told Rosset that "to read this is to take the cure." Later Barney told me what about the book had make him postpone its publication for nearly a year.

BARNEY ROSSET: Publishing it was like taking off into an abyss. It went far, far, far beyond Tropic of Cancer This was Star Wars!

When the international press reported that Mary McCarthy and Norman Mailer had told a 1962 Edinburgh Art Festival audience that Naked Lunch was a work of genius, Barney printed and bound 12,000 copies and put them in a warehouse. His hope was that Grove Press would shortly win a Supreme Court case involving Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer that would free that book for the entire country and make it possible for Grove Press to go ahead with the seemingly more dangerous Naked Lunch. In fact, however, Barney couldn't wait.

After I read Naked Lunch and told Barney it was an important book, perhaps a great one, and that we should win any case involving it, if necessary in the Supreme Court, Barney brought Burroughs' masterwork out. Six months later the Supreme Court did act to free Tropic of Cancer in a case arising in Florida that I took up to the Court (Grove Press v. Gerstein).

A few months after the Tropic of Cancer victory, a book dealer in Boston's Combat Zone was arrested for selling Naked Lunch. So I began preparing for the novel's defense by talking to Allen and other prospective expert witnesses about the novel's literary, artistic and other social importance and by locating articles and reviews published about it in literary journals and newspapers in the United States and other countries.

Before the criminal trial took place, the Civil Rights Division of the Massachusetts Attorney General's Office agreed to my proposal that the criminal proceedings be suspended in favor of an in rem action against the book itself, as permitted under Massachusetts law. This allowed Grove Press directly to take over the defense of Naked Lunch, and to advocate its entitlement to constitutional protection. The book's entitlement to freedom from censorship would now be the only issue in the case.

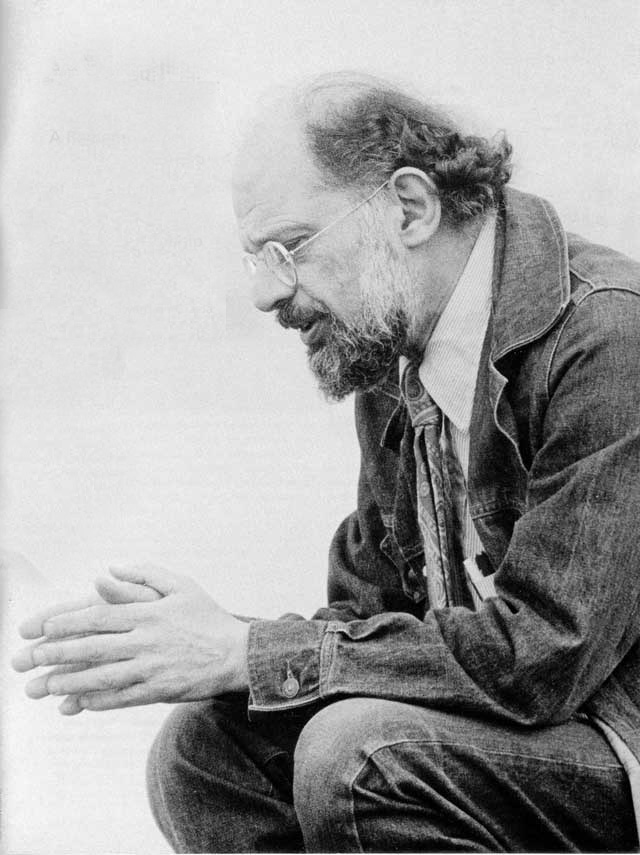

Allen would be the principal and last of seven Grove Press expert witnesses to take the stand. In those days he did not look like a professor of creative writing, as he did some years later when he came to an Individual Liberties class of mine at Cardozo and rattled law school rafters with his protests against America under Ronald Reaganism by reading aloud his poem Birdbrain. In the Boston courtroom, with his great shaggy beard, balding pate, and mane of long stringy hair, Allen looked like the Lord of the Beatniks. When he took the witness stand, however, Allen tried to make a good impression on the judge by wearing a white shirt, a figured tie, and a jacket for what I like to think was the first time ever.

The presiding Boston Irish-Catholic Judge Eugene A. Hudson peered down at the New York Jewish-Buddhist poet and said "straighten your collar!" He seemed to regard Allen as a schoolboy who had come up to the front of the room to recite his lessons. The poet responded by straightening his collar, peering up at the judge, and saying "Yes, sir."

And then, responding to my questions-among those that he and I had developed together sitting with our backs against the floor-to-ceiling windows of a funky penthouse suite I had taken in a fine old Boston hotel, Allen mesmerized the courtroom. He had a magnetic, hypnotic way of speaking about things he cared deeply about, and he cared deeply about Naked Lunch, and Burroughs, and freedom of expression. He talked virtually without interruption for nearly an hour about the structure of Burroughs' novel and about the social and political importance of its images and ideas. It occurred to me that Allen understood the novel even better than Burroughs did.

Citing chapter and verse from memory, he brought out the way in which Naked Lunch conveyed criticism of the state's control over people - sexual control, political control, social control - and detailed Burroughs' theories about the American police state, mass brainwashing, and the workings of modern dictatorships. He delivered detailed expositions of the political parties and groups portrayed by Burroughs - the "Factualists," the "Liquefactionalists," the "Divisionists," and their counterparts in modern American political life. He pointed out that in Naked Lunch Burroughs predicted and parodied antiNegro, antiNorthern, and anti-Semitic Southern white racist bureaucrats. He revealed that the novel's unity was that of the cycle of drug addiction and withdrawal, and he credited Burroughs with having importantly influenced the work of many poets and authors, not least of all himself.

Allen argued that Naked Lunch was "an enormous breakthrough into truthful expression of really what was going on inside Burroughs' head, with no holds barred" and that it contained "a great deal of very pure language and pure poetry, as great as any poetry being written in America today."

Allen also explained why the novel's surrealistic mosaic style, its lack of plot in the traditional sense, its "shadowy" characters, its capacity to be "sliced into" almost anywhere, did not mean that it was absent a coherent plan.

Although the Massachusetts Attorney General called no witnesses at all, in the end - who, really, was surprised? - Judge Hudson declared Naked Lunch to be "obscene." He said that Burroughs, "under the guise of portraying the hallucinations of a drug addict, had ingeniously satisfied his personal whims and fantasies, and inserted in this book hard-core pornography."

JUDGE EUGENE A. HUDSON: While we have to take the book as a whole, from cover to cover [as Justice Brennan in the Roth case had stipulated was constitutionally required] I am somewhat concerned as to whether or not an author has the license, poetic license, if you wish, to escape responsibility in his writing, so far as it concerns hard-core pornography, by describing it as hallucination ....

Of course, what we are dealing with is a remarkable work when we refer to Dante's Inferno. That is a classic and we recognize it as such; but at the same time it hasn't the four-letter words and it hasn't the freedom of expression that we have in this book here. There are subtle references to, for instance, the anus is referred to, in Dante's Inferno, and there are some sordid scenes described in Dante's Inferno, but it is done with the tone and with a literary flair that the most chaste person couldn't take exception to ....

I interrupted the judge's soliloquy to say that I did think the Inferno "was shocking when it first appeared."

JUDGE EUGENE A. HUDSON: In its day?

ALLEN GINSBERG: It was!

JUDGE EUGENE A. HUDSON: Well, history perhaps teaches us that it was shocking to people of that day... But what are we headed for? I want to know. My mind is entirely open as far as this book is concerned, but let's project ourselves into the era that Mr. Burroughs projects himself into in relation to these political parties that you refer to, Mr. Ginsberg. Is it conceivable that in our lifetime, or in the lifetime of the next generation, that there will be no censorship whatsoever, so far as freedom of writing and publishing is concerned?

No censorship whatsoever? That was exactly what Allen, Bill Burroughs, Barney Rosset, and I were striving for.

A few years ago, I spoke to our leadoff witness at the trial of Naked Lunch, Norman Mailer; it was while I was working on the story of the struggle for literary freedom in America that became my book Girls Lean Back Everywhere: The Law of Obscenity and the Assault on Genius (Vintage, 1994). Mailer reminisced about the Boston trial and Judge Hudson:

NORMAN MAILER: He was a big florid Irishman, and terribly cordial to me. Couldn't have been nicer. He didn't like Allen much, didn't like the look of him. But he was almost courtly with me and I remember feeling uneasy about that: he was being too nice. I had that experience over and over, in about three or four cases now, where the judges were very nice to me and we lost. So I get nervous when judges are nice; I figured that's the last bit of goodness they're going to give to you. They greet you cordially and say "I'm so pleased to have you in my courtroom, Mr. Mailer," and after that, watch out!

Hudson was so friendly to me that he did rattle my brain a little. But I always thought it was insane. I thought there was no way we could win. I come from the gloomy days of the '30s and '40s when you just never won those kinds of cases. There's been the Woolsey decision on Ulysses ... well, that was James Joyce's Ulysses. And I thought Naked Lunch was truly going to be seen as an awfully obscene book. Frankly, I didn't see any hope of winning, but then, on the other hand I did. Because you [de Grazia] were so cheerful about it. And, you know, you get on a team and if everyone's saying we're not going to lose, you do try to win. But I wasn't surprised or shocked when we lost. I was startled when we won, when the appeal was won ....

On July 7, 1966, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that Naked Lunch could not be considered obscene under the doctrine developed by Justice Brennan in the US Supreme Court. The decision to free Naked Lunch was a major victory for artistic freedom in the States, and Allen was as responsible for that victory as anyone else connected with the efforts to free Burroughs' book. We lost the trial but we won our appeal because of the record of literary, artistic, and social "importance" that our defense team had built. That was what Justice Brennan, in Roth, had implied would be necessary to win; and in the Florida Tropic of Cancer case Brennan had said that would be sufficient to win - no matter how "obscene" the book might seem to policemen, prosecutors, and judges. Because, said Brennan, the constitutional status of a work cannot "be made to turn on a 'weighing' of its social importance against its prurient appeal." Unless it was "utterly" without social importance, a book could not be branded obscene. This "bright line" test of freedom for literature and art guided the country's federal and state court obscenity decisions during the next several critical years.

However, I ought to record what else Mailer said to me when I talked with him that time:

NORMAN MAILER: Every gain of freedom carries its price. There's a wonderful moment when you go from oppression to freedom, there in the middle, when one's still oppressed but one's achieved the first freedoms. There's an extraordinary period that goes from there until the freedoms begin to outweigh the oppression. By the time you get over to complete freedom you begin to look back almost nostalgically on the days of oppression, because in those days you were ready to become a martyr, you had a sense of importance, you could take yourself seriously, and you were fighting the good fight. Now, you get to the point where people don't even know what these freedoms are worth, are using them and abusing them. You've gotten older. You've gotten more conservative. You're not using your freedoms. And there's a comedy in it, in the long swing of the pendulum ....

I believe the Howl, Tropic of Cancer, and Naked Lunch decisions changed the literary landscape of America for good. And the I Am Curious-Yellow decision in 1969, reached by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York, did the same thing for motion pictures. Those decisions opened up authors, publishers, and print distributors, and movie writers, directors, and exhibitors. After that, American writers and publishers and film-makers felt free to create, print, and exhibit almost anything. I think Allen would agree that, after those decisions, there was little in "obscenity" law for poets and novelists and screenwriters to worry about anymore.

{* The raids made by Oklahoma City police last year on the Oklahoma County Metropolitan Library, Blockbuster Video, and the private home of an ACLU staff member, resulting in the seizure and threatened destruction of seven videotape copies of the Academy Award-winning motion picture The Tin Drum under a local "child pornography" law suggest that the courts have not yet provided equal constitutional protection from government officials' attacks on artistic work involving minors.}

Allen was a major force in the struggle to gain full freedom of expression in this country for serious artists and writers and their publishers. But not only for them. At about the same time as the Naked Lunch decision, the Supreme Court unpredictably upheld the conviction of mail-order publisher Ralph Ginzburg because the court said he promoted EROS, Liaison, and The Housewife's Handbook of Sexual Promiscuity in a way that "pandered" to the prurient interests of the average American and thereby neutralized the claim to social importance. Allen's response was to travel to Washington and picket the Supreme Court.